Packaging inspection is machine vision’s bread and butter, so to some extent the advances happening in the vision sector - the introduction of AI, for instance, as well as shortwave infrared imaging becoming more accessible - are now finding their way onto packaging lines.

Machine vision technologies are widely used for a range of purposes in packaging inspection – with key applications including presence verification, alignment, label inspection and print inspection, as well as product handling, pick-and-place and packaging logistics. As Simon Hickman, managing director at Multipix Imaging, explained, many of these tasks are relatively simple and lend themselves to what he described as smart sensor or smart camera technology, where the image processing is performed by a processor inside the camera.

‘These [smart] cameras are becoming more capable and user friendly, which makes them a good choice for many packaging inspection tasks,’ he said.

Smart cameras are, however, less suitable for multi-view or high-speed applications, and they generally do not have the processing power for complex tasks. For example, Multipix developed and set up an automated quality control system to inspect disposable plastic mouldings at rates of up to 1,200 parts per minute. This system required a PC for processing.

Hickman explained that the system was designed to detect and expel defect parts and reduce damage waste to zero. ‘It was necessary to inspect parts from multiple angles to ensure all sides were free from damage,’ he said, ‘and to perform optical character recognition of the cavity number at the bottom of the part.’

A second camera measured the diameter and a third camera measured the height and profile to complete the full inspection. ‘Handling data from three cameras at these speeds required a PC-based system with the power of Halcon software processing,’ Hickman said.

Well baked

One task where a vision system can be employed is to inspect how the product is presented to the packaging machine. In the case of food, it also needs to be inspected for damage or poor quality that wouldn’t be accepted by a supermarket.

‘The product also has to conform to maximum dimensions and shape,’ explained Paul Wilson, managing director of Scorpion Vision, who gave the example of packaging bakery items. ‘If they [baked goods] are too big, they may not fit into the packaging and can cause a blockage at the wrapper, causing the line to stop,’ he said.

‘So, inspections might include colour and size and perhaps orientation, but each product type comes with a specific challenge that can cause blockages, so there are often additional inspections required for those scenarios,’ he added.

According to Wilson, some quality checks before packaging might simply result in the product being rejected from the line. One example is a system Scorpion has developed for flatbread tortilla inspection, which inspects an impressive 45,000 tortillas per hour.

‘Such a fast production line cannot rely on human inspection, and it is critical that every single product is inspected,’ he said. ‘This system consists of a line scan camera that builds an image of every tortilla as it passes under the camera. Anything that does not meet the parameters, such as size, shape – circularity in this case – and other constraints are ejected using pneumatics.’

Mature cheese

Wilson also cited another solution devised by Scorpion for a challenging problem experienced by a cheese producer. As he explained, the producer cuts cheese wedges from a large drum of cheese and sends them through a wrapper, after which the cheese is weighed and then labelled. However, the labeller experienced what Wilson describes as ‘a real headache’, because the process was based on a mechanical system that placed the label on the cheese in an approximate location and often not very straight – forcing the producer to manually re-label as much as 60 per cent of the cheese.

A robot vision system was developed to place labels on wedges of cheese. Credit: Scorpion Vision

‘The source of the problem was the inconsistent shape and size of each cheese wedge, whereby no mechanical system could cope with placing the label precisely on the pack. Instead, we designed a 3D robot vision system that could locate the side of the wedge to identify where the label should be placed,’ he explained.

‘The system measured the orientation and angle to provide coordinates so that a robot could locate the label in exactly the correct position, ensuring it was central and straight,’ he added.

Sustainable materials

Another company active in this area is the electronics multinational Omron, which has developed vision technology used at many of the main stages of the packaging process. As Jamie Steed, EMEA product marketing manager for vision and traceability at Omron, explained, the primary and secondary packaging process can often have similar types of inspection requests – depending on the product type being inspected, this can also be the consumer-facing packaging.

‘Manufacturers are looking to protect their brand integrity and use more sustainable materials in the packaging process, as the appearance of the product is a key feature. One way to ensure brand integrity is the use of a machine vision inspection system in the packaging process. These are often added to prevent faulty products entering the supply chain,’ he said.

One common application of vision technology in the primary and secondary packaging segments is label inspection – an area where Omron has introduced a new fine-matching AI algorithm to check label artwork for defects.

Another common application is checking the position of the label to make sure it is placed accurately. ‘This is often solved by detecting a feature on the label artwork and referencing this point to the edge of the packaging. The vision system can then calculate the offset and reject the product if it is out of tolerance,’ said Steed.

Correct lighting and illumination

As with all vision applications, Steed stressed that working with a good image is essential and selecting the right illumination is a critical part of the process. In an effort to ensure these critical criteria are met, he also noted that Omron’s latest smart camera, the FHV7, comes with multi-colour LED lighting, allowing users to select the best light for the application.

‘Another key application area we have looked at is cap colour and cap placement – and the placement of key drivers behind caps to prevent leakages. The camera is placed after the capper to investigate if the cap has been applied squarely and fitted to the correct level. This is often done by placing an LED light behind the bottle and cap to create a silhouette image,’ he said.

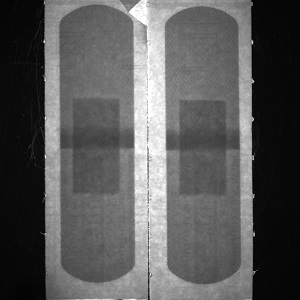

Shortwave infrared imaging can be used to image products through plastic packaging, as well as check for fill levels in bottles. Credit: Omron

After the camera has acquired the image series of edge tool algorithms, Steed said it can check to see if the cap is within tolerance and, if not, a signal will be given to a reject mechanism.

‘Lines can run at very high speed and a second output can be used to stop the line if there are too many consecutive failures,’ he said.

The third stage is tertiary packaging, which protects the product when in transit. Typical vision applications can be used to check if the contents of the packaging are complete, as the tertiary packaging normally contains multiple items of the primary or secondary packaging.

Future innovations

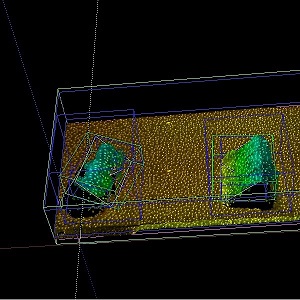

This autumn, Steed revealed that Omron is set to launch a range of shortwave infrared cameras manufactured by Omron Sentech – initially with a GigE interface in 0.3MP and 1.3MP resolutions.

‘SWIR imaging allows users to solve applications that are invisible to the human eye,’ Steed explained. With a SWIR camera, lens and LED light, operating from 900nm to 1,650nm, the user can detect clear liquid droplets that could indicate a leaking product, for instance, or check the fill level in an opaque plastic bottle, as SWIR can image through plastic.

‘Additionally, it is possible to penetrate thin films and printing on packaging with SWIR technology, meaning in certain applications the camera can see inside the package – allowing machine vision tools to inspect the actual packaged item,’ Steed added.

Looking ahead, as human labour becomes more expensive, Wilson predicted there will be even greater pressure to increase automation. Scorpion Vision has designed vision systems to automate some very complex tasks for trimming and processing fresh vegetables, tasks that would otherwise require a human operator.

‘It's the availability of 3D vision and AI that can now supplement or replace the human trimmers, as a 3D vision system can look at a vegetable and decide where it needs to be cut,’ Wilson explained. ‘AI is used to great effect here, as it can make the final decision – this is the key to high-yield, low-waste automated produce processing and packaging. We have delivered systems using this technology for growers of leek, turnip and swede for example, and the demand for more developments in this area is significant.’

Meanwhile, Hickman observed that, moving forward, there is no doubt that AI will play a major role in future development, but cautions that it is not the answer to everything.

‘We must all remember that the core of any camera inspection system is the quality of the images, and this requires vision knowledge – selecting the most appropriate camera, lighting, lens and analysis technique will always separate properly engineered solutions that are truly robust and reliable,’ Hickman concluded.