Packaging can vary from the functional to the iconic. Andy Warhol famously turned the Coke bottle into art with his 1962 silkscreen painting ‘Green Coca-Cola Bottles’, a print of rows of regular, yet individual Coke bottles. Coca-Cola patented its fluted glass bottle in 1915 to protect against copycats, and the design, inspired by the ribbed elongated shape of a cocoa pod, has since become synonymous with the drink.

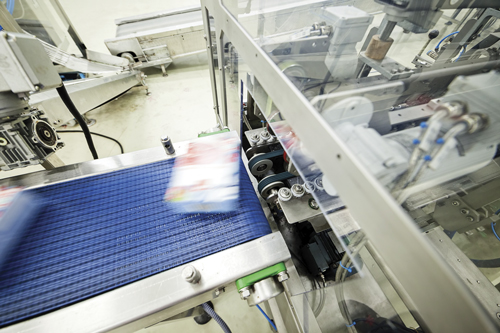

If the Coke bottle is the iconic, then the functional is packaging’s ability to keep food fresh for longer. One of the highlights of the Interpack trade fair, taking place in Düsseldorf, Germany at the beginning of May, is its Save Food area displaying packaging solutions designed to reduce food waste. The Save Food convention will also be held on the first day of the show, organised in partnership with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation and the UN Environment Programme.

Quality control on highly automated packaging lines is normally ensured by machine vision, to check print – making sure Coca-Cola’s logo is the right shade of red, for instance – and that containers are sealed properly to avoid food spoiling. Fynbo Foods, a Danish manufacturer of jams and preserves, has installed 3D vision sensors from Sick to inspect whether its jars are hermetically sealed. Sick’s TriSpector1000 gives a 3D profile of the lid, which will be flat if the jar has been successfully pasteurised and the contents under vacuum, but will have a button pop up on the lid if it isn’t sealed. ‘These sorts of quality inspection help reduce food waste by minimising poorly sealed jars where the jam or preserve would spoil,’ commented Matthias Mezger, head of industry cluster consumer goods at Sick.

At an earlier stage in the packaging process, machine vision checks print quality where, according to Dr Ullrich Schramm, key account manager at Isra Vision, inline colour measurement is a growing requirement. ‘Customers want, firstly to have quality monitoring of spot colours for brand customers like Coca-Cola, Procter and Gamble, the big global brands, which specify printed colours with a very narrow tolerance range,’ he said. Here, colour inspection has to be inline, giving continuous colour monitoring during the print run.

‘Besides quality issues, a flexible packaging printer would also want to use inline colour measurement to reduce the setup time of the printing press,’ Schramm continued. The inspection system gives the operator information about colour deviation from a target value at an early stage in the print run. ‘The essential point is that the system shows the deviation of the correct colour value to the target colour – how far the print run is away from a certain red, for instance – and it has to be able to do this without stopping the machine,’ he explained. Making sure all colours are within tolerance has the potential to save time and material in the printing process.

Isra Vision offers 100 per cent inspection systems for quality control of flexible packaging, the kind of thin plastic, sometimes laminated with aluminium or metal foils, used to package food and various other products.

The company provides inspection all along the workflow, starting from quality control of the plastic extrusion process for flexible packaging or checking for coating defects on foils. The web material is then run through a rotogravure or flexographic printing press, and laminated and converted to create the finished packaging. Inspection systems are employed before printing to look for gels, black specs, inclusions, and coating defects, and to look for spots, splashes, streaks, and colour deviations during printing. Cameras might also be used to look for inclusions or voids during lamination.

Line scan cameras are used for web inspection. Typically web widths in flexible packaging printing, according to Schramm, are 1,000mm to 1,600mm, and normally one or two cameras would cover that working at a measurement resolution of 150µm to 300µm.

‘You want to use as few cameras as possible,’ Schramm remarked, and so high resolution cameras are typically used. The printing process is also getting faster, with Schramm saying that flexographic printing machines now run at 600 to 800 metres per minute, sometimes 1,000 metres per minute. The goal is to get as much data at this high speed as possible. Isra Vision uses line scan cameras with a resolution of 4,000 to 8,000 pixels, with the system acquiring a new line every 150µm to 300µm to build up an image of the web. ‘The challenge here is that creating data every 150µm in the machine direction, you need a lot of lines per second – 600 metres per minute is 10 metres per second, and at 150µm resolution that is more than 65,000 lines per second, which has to be acquired and processed. This is a high data rate,’ Schramm noted. ‘One of the advantages of Isra’s inspection systems is that the company offers a dedicated processing module in the PC, which is programmable for surface inspection or print inspection tasks, in order to handle data acquisition and the first stages of data processing. The challenge in these sorts of application is to handle data processing while meeting the speed and resolution requirements.’

Another challenge Schramm highlighted for inspecting these films is dealing with the flexibility of the substrate. ‘If you don’t account for production tolerances when inspecting thin and stretchable materials, such as the hygienic films, you create a lot of false alarms,’ he said. Isra Vision has a special compensation algorithm to deal with production tolerances, such as web wander, web stretch, and tolerable registration tolerances.

Smarter inspection

The environmental impact of packaging is now much more of a consideration – one of Coca-Cola’s bottles, launched in 2009 and called the PlantBottle, is completely recyclable with 30 per cent from plant materials, such as sugar cane.

‘Packaging lines want to reduce waste, so companies want to inspect not only at the end of the process but also carry out a continuous quality check,’ Mezger at Sick observed. He continued: ‘Factories want to use this data to improve the inline process, to make the previous machine run more effectively.’ Mezger gave the example of inspection data on the form or colour of baked goods giving information on how well the ovens are operating. ‘This is an example of the potential of digital production equipment. Sensors in packaging lines are generating more data, and in the future this data will be sent directly into an enterprise resource planning software or other system, which could be cloud-based.’

Packaging lines also now have to deal with shorter print runs and custom brand campaigns, according to Amir Dekel, vice president at Isra Vision, which is another reason why packaging and print companies are using digital production processes.

‘Intelligent image processing systems and seeing sensors create the scope to provide completely new solutions, particularly in the context of Industry 4.0,’ Mezger said. ‘Binary assessments such as “yes or no” and “good or bad” are replaced by the development of individual applications, which are based on a wide range of data and intelligent evaluations of said data. This opens up unimaginable horizons of availability for industrial production processes.’

Sick has made vision sensors from the InspectorP product families, for example, open and programmable, which means integrators and end customers have the scope to integrate their own applications into the sensors.

Some of the process data needs to be analysed in real time, explained Mezger, which will be sent over a programmable logic controller (PCL), while other more generic data, that might not be time critical, can be analysed at a later date.

Sick provides different kinds of inspection system, including 3D cameras for use where depth information is helpful. One of Sick’s customers, for instance, uses 3D vision to grade oysters based on volume, and transfers this information to the packaging machine.

‘In primary packaging, it’s important to analyse the product itself,’ explained Mezger. He gave the example of measuring a chocolate bar to ensure it is coated with enough chocolate and that the volume is correct. ‘Primary packaging inspection is a growing market, but it’s also a challenging one because it is high speed as well as requiring high accuracy and repeatability,’ he added.

Inspection of secondary packaging is more about checking whether the packaging corresponds to the product inside, said Mezger.

Sick will be demonstrating 3D vision solutions and other equipment to support the packaging sector at the Interpack trade fair in May. The company’s TriSpector1000 is an example of an integrated 3D smart camera with onboard processing and lighting, which Matrox Imaging’s product line manager, Pierantonio Boriero, noted is becoming more common on packaging lines. Matrox Imaging offers its own smart cameras, such as its Iris GTR 2D imager that includes an embedded processor for image analysis.

‘A traditional vision setup for packaging line inspection involves three major pieces [of equipment]: a source of illumination such as an LED array; a camera to capture the image; and a vision controller or PC to process the image,’ Boriero explained. ‘However, with the advent of embedded processors, cameras could be enhanced with the functionality of a computer, leading to smart cameras with vision controllers integrated in them. So there’s still a need for those three components; however, it’s possible to have one built in to another.’

Boriero noted that Matrox has made advances in colour relative calibration for consistent colour-based analysis, and in code reading algorithms for traceability purposes, both of which have benefits for packaging inspection.