In 1986, Matrox Imaging demonstrated a device able to run 3 x 3 convolutions on a 640 x 480-pixel image in real time using a graphics chip. This was the first PC-based image processing accelerator, and it was ‘unheard of in our industry back then,’ recalled Sam Lopez, senior vice president of sales and marketing at Matrox Imaging.

The device came about thanks to Matrox co-founder Lorne Trottier’s experience with graphics cards. He came up with the idea of using a graphics engine in reverse to drive memory, and using the chip to run convolutions and histograms and implement image processing algorithms. CPUs in PCs were extremely slow in 1986, and here was a vision engine that didn’t rely on the host CPU for processing.

‘That’s what I like doing, looking at technology and figuring out how to apply it,’ Trottier told Imaging and Machine Vision Europe. ‘We were already kind of into image processing, so we knew about needs for image processing. I knew about this particular graphics chip, so I figured out that I can use it for image processing.

‘That’s the kind of thing our creative people do at Matrox all the time,’ he added. ‘That’s what’s fun about this, there’s always new technology coming out and more difficult problems to solve, and figuring out how to use that technology in clever ways to solve those problems is what we thrive at here at Matrox.’

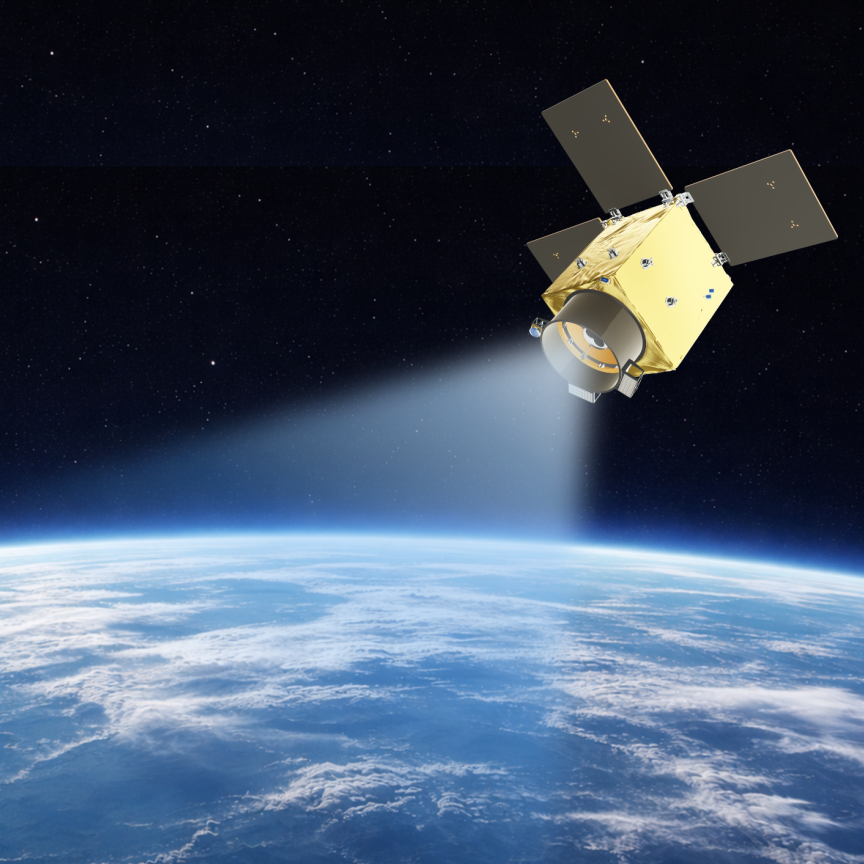

The MVP-AT accelerator – which was used by Nasa in the early 1990s, for instance, in a satellite data analysis package called PC-Seapak – is just one example of the pioneering work done at Matrox.

Trottier and his co-founder started the company in 1976, in the early days of the microprocessor. The idea was to build an interface between microprocessors and video. ‘The bidirectional in and out of the microprocessor was the core idea that started the company off, and has been a theme throughout its history,’ Trottier said.

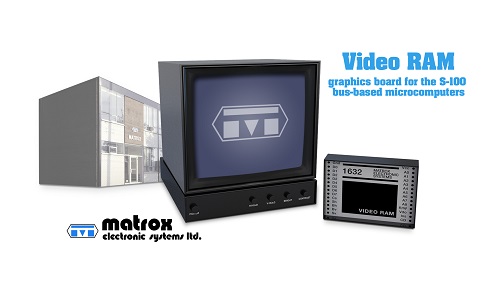

Matrox’s first product was called Video RAM, a controller for a microprocessor to display computer-generated alphanumeric data. It was called Video RAM because the ACSII text, the binary code for characters, was mapped to memory.

‘You didn’t have to know anything about video,’ Trottier explained. ‘If you knew about RAM you could connect the RAM to your microprocessor, and as soon as you used ACSII text it was displayed automatically.’

Years later a different Video RAM technology was developed for graphics cards. At one point, Trottier got a call from the president of Micron asking about Matrox’s Video RAM to see if Trottier could help out in a patent dispute Micron was having with Texas Instruments over VRAM. ‘I told him that the only similarity between our VRAM and the one you’re talking about is the name,’ Trottier said.

Matrox began life very much as a personal project between the two founders. The company’s first phone line was installed in the Trottier family home, with Lorne’s mother acting as receptionist. Two months after Matrox’s founding, Trottier visited a computer trade show in Atlantic City in July 1976, collecting data sheets from a number of small start-ups in the early personal computer space, among them a datasheet from the Apple I, which he still has in his archives.

Matrox’s first product, Video RAM, in 1976. Credit: Matrox

Its pioneering spirit led Matrox to develop some of the earliest frame grabbers, a foundation that is in evidence today – Matrox still makes frame grabbers. ‘Exactly when image processing started [for Matrox] is hard to say,’ Trottier said. The first frame grabber Matrox designed was in the late 1970s before the PC came out, for Intel’s multi-bus board-level computer. ‘Hardly anyone had done digitised video because it was high bandwidth back then,’ he recalled. ‘We used an A/D converter that cost $600 a chip – in the 1970s – to digitise video on our frame grabber.’

The price of those chips came down rapidly, and once the PC was introduced in the early 1980s, Matrox was the first to build a frame grabber for the PC. ‘Exactly where along the road machine vision came in is a little fuzzy,’ Trottier said. ‘Those frame grabbers were used for all kinds of things back then; there were all kinds of research projects going on and machine vision and image processing was one of them.

‘Back then image processing systems were mini computers and cost a fortune,’ he continued. ‘We were one of those pioneers that brought the prices down and made it much more accessible.’

In the early 1990s, the company split into three divisions: Matrox Graphics, delivering graphics solutions; Matrox Video, for the broadcast industry and digital video editing; and Matrox Imaging, focusing on component-level solutions for machine vision applications. The unified thread underpinning the Matrox model remained the original notion of interfacing between microprocessors and video.

In the early 1990s, Matrox Imaging decided to develop an imaging software library, releasing the Matrox Imaging Library (MIL) in 1993. By this time the company had a lot of different frame grabbers, and the software to support the MVP-AT accelerator was getting hectic, Trottier said, so MIL was created as a uniform library that worked on all Matrox products. ‘That was a key thing, and was one of the reasons why we kept customers for such a long time,’ Trottier added.

Today, Matrox Imaging’s portfolio includes frame grabbers, smart cameras, and software libraries. Credit: Matrox

More recently, Matrox Imaging has released Matrox Design Assistant software, which takes away the need for programming by using flowcharts to create a vision application. Both MIL and Design Assistant now have deep learning functionality, which can solve problems that couldn’t be solved with classic rule-based image processing tools.

One of the newest cameras from Matrox Imaging is the Matrox AltiZ 3D profile sensor, with a dual optical sensor design and data fusion capability. The camera’s two sensors reduce occlusions found in more traditional laser profilers to give more complete 3D coverage of a scene.

‘The combination of 2D and 3D, classic image processing, deep learning, with robotics, allows you to make some extremely powerful solutions,’ Trottier said. ‘When you integrate those pieces together you have something that’s amazingly powerful.’

Trottier said that there are new areas that have a big demand for machine vision, highlighting the electrification of automobiles as one example. He said: ‘Just the assembly of batteries and battery packs is a whole new sub-industry that’s emerging,’ and that Matrox Imaging is getting customers in that area.

Lorne Trottier co-founded Matrox and has now acquired full ownership of the company. Credit: Matrox

Lopez noted that the reduction in cost plus the reduction in complexity for implementing machine vision systems has ‘opened up a lot of new opportunities in industries where they couldn’t afford to put vision in the past’. He said that standards, whether that’s video standards, but also communication protocols to communicate with other devices like robots or PLCs, is lowering the complexity of vision systems. Matrox is active on a number of standardisation committees, including Coaxpress and GigE Vision, to help define and develop those standards.

Lopez added: ‘There’s going to be more competition going forward as the technology becomes more accessible and easier to use. There are a lot of good ideas out there that merit attention. We don’t discount even the start-ups, which could come up with some interesting things moving forward.’

Trottier said that his advice for start-ups is to work with companies to get exposed to real imaging needs. ‘That’s the catalyst,’ he said. ‘If you become aware of needs and aware of new technology, you’ll figure out new solutions.’

In 2019, Trottier acquired full ownership of Matrox, declaring renewed commitment to customers, suppliers, business partners, and employees.

‘For 45 years to remain viable and profitable we’ve endlessly had to reinvent ourselves,’ Trottier said. ‘That’s one of the things I love about this industry. I’m a techno-geek myself; I started fooling around with electronics, building crystal radios when I was a kid. This is a continuation in a way. Most of the engineers we have working for us have the same geeky love of technology, and we love staying on the leading edge, and figuring out what the newest technology is and how it can be applied to solve real-world problems.

‘In the area of machine vision there has been no lack of innovation and new technology,’ he continued, ‘and we’re right on the forefront of some of those things, including things like 3D... and deep learning – we have customers in many projects applying that [deep learning], all of which is very exciting.’