The history of Finnish spectral imaging company Specim reflects to a certain extent the rise of hyperspectral imaging as an inspection tool. When the company began 22 years ago as a spin-off from the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, it had only one or two competitors that could supply similar equipment. Today, according to Esko Herrala, director and one of the founders of the company, ‘there are around 45 different companies providing instruments that can be called spectral imaging devices.’

Twenty-two years ago, Specim’s customers were exclusively universities, but five years ago the company changed its strategy to target industrial firms and machine vision integrators and, in June 2016, launched the first industrial hyperspectral camera in its FX series. ‘We realised that now is the time when more industrial customers are aware of this kind of spectral technology and the possibilities it offers,’ Herrala said.

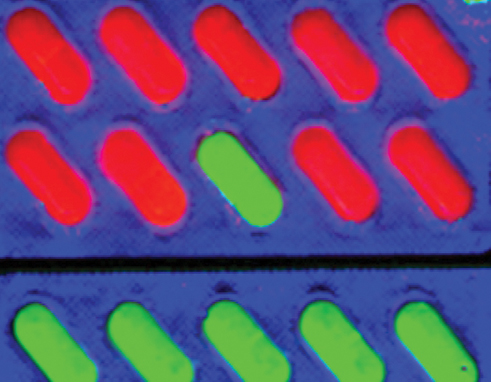

Hypersectral imaging can give the chemical composition of tablets through the blister packaging

‘We have thought for a while now that in the long run spectral imaging is going to be a new kind of machine vision tool. Inspection has progressed from black and white cameras to RGB colour cameras; today, 3D imaging is more prevalent and vision users are looking for new tools for process quality measurements,’ he continued.

The hyperspectral imaging market is expected to be worth $11.34 billion by 2022, according to a study by Zion Market Research. Zion’s report mentions Specim as a key European supplier.

The company has launched two products in its FX series thus far, the FX10 and FX17, which cover the near infrared regions of 400nm to 1,000nm and 900nm to 1,700nm respectively. More models are planned in the series. Both cameras have 224 spectral bands, with the FX10 offering a frame rate of 330fps at full frame, while the FX17 gives 670fps full frame, both designed to fulfil the demands of industrial customers.

Specim bases its cameras on ‘push broom’ line scan sensors, which image objects by either moving the camera or the part. The push broom method of building up an image was employed for spectral imaging 20 years ago and Specim is sticking with it. ‘We think this [push broom] is the only technology that’s suitable for industry, where the signal-to-noise ratio and the light gathering ability are important,’ Herrala commented.

Herrala said that, while availability and reliability of spectral imaging cameras are improving, there is still a lack of knowledge about the technology. ‘Most machine vision system integrators don’t know about spectroscopy or what it means to measure outside the visible wavelength range,’ Herrala remarked. ‘They are accustomed to illuminating at visible wavelengths and they know what to expect from visible imaging.’

Hyperspectral system suppliers are putting more effort into educating machine vision integrators and end-users about the potential the technology holds. In Europe, Stemmer Imaging, which distributes Specim’s cameras, now runs spectral imaging training days throughout the year, where attendees gain practical insight into what the technique can do and how to solve certain problems using spectral imaging. ‘This is valuable work,’ Herrala said. ‘The main task at the moment is education.’ Specim is also preparing webinars and articles to raise awareness of the technology.

The transfer of knowledge occurs both ways, with system suppliers like Specim learning from their customers. ‘Every day I’m surprised about what our customers are doing; new applications, new problems solved that can’t be solved with current machine vision technology,’ Herrala said.

Herrala believes hyperspectral imaging is already in a position to serve new industrial users. ‘Specim’s instruments are pretty much ready; we know what we can deliver, they have standard connectors like Camera Link and GigE Vision, and there is a lot of software available for this technology,’ he said.

Processing power has also increased, important for making sense of the large volumes of data generated by hyperspectral imaging. Nvidia’s latest GPUs, for instance, give parallel processing capabilities that can be used with spectral cameras.

Turning to professional groups

Hyperspectral cameras have established a foothold in industry to a certain extent and Specim will continue to promote and supply industrial customers, but it is also looking to broaden its customer base to include professional groups like doctors, police or farmers, which Herrala feels have a need for spectral imaging.

The infiltration of spectral imaging into these professional markets might take three or four years, according to Herrala, and will rely on products being less complex and give results without the user even knowing that they are based on spectral imaging. One example would be monitoring the growth and health of plants in greenhouses and on farms, where the instrument could be used to tell farmers when they need to apply fertiliser.

The uptake of hyperspectral imaging in these applications will be significant for the future development of the technology. ‘These professional groups are the most interesting future path for where spectral imaging is going,’ Herrala confirmed. This cannot happen, however, according to Herrala, without an increase in awareness of the technology’s potential. ‘The main problem is that only a relatively small number of people understand spectral imaging and what it can do,’ he continued. ‘We need more education to increase the use of spectral imaging. We try to forget the technology and try to start talking about applications, asking the question: “What can we actually do with this technology?”

‘People are not talking about spectral imaging, they are talking about applications,’ he added. ‘They are saying: “I can detect cancer with this instrument”, “I can detect fungus in my greenhouse”, or “I can detect whether my plants need watering”.’

Herrala believes that practicality will be a key factor in the uptake of hyperspectral technology by these professionals. ‘These groups need the analysis result immediately on site – they don’t want to send samples to a laboratory for analysis – and based on the result they can make some kind of diagnosis or decision on how to proceed.’

Dedicated spectral cameras are one thing, but the technology will reach new heights in terms of adoption when it is used on mobile phones, and it seems this will only be a matter of time. There were spectroscopy solutions designed for mobile devices on display at SPIE Photonics West, the photonics trade fair in San Francisco from 28 January to 2 February – Si-Ware Systems was one company exhibiting its spectral technology for smartphones. In addition, late last year, scientists from VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, the centre where Specim originated, launched a hyperspectral device for smartphones based on a micro-opto-electro-mechanical system (MOEMS) filter.

Incorporating spectral imaging on a mobile would allow people to do things like check food is ripe while they are in the supermarket, for instance.

Specim's headquarters

Although it has plans to supply professional groups with its hyperspectral systems, Specim’s main customers will, at least for the short term, continue to be industrial users. Europe is currently Specim’s biggest market at around a 40 per cent share, with Asia close behind at around 30 per cent. Most of the rest is US and Canada, said Herrala. The company delivers instruments to 35 countries including South Africa and South America, but these are minor markets. The highest growth is in Asia – in China, Korea and Japan.

In designing its FX series, Specim turned to its customers to establish what they required from hyperspectral technology. Herrala said: ‘The feedback now that the cameras are in production has been very positive; at the moment we are getting more orders than what we can deliver. It shows that there is a demand for these kinds of cameras.’